Canadian statehood presents a challenge for protectionist

There's no fundamental difference between state level and country level trade barriers

Since his first meeting with Trudeau in December, Trump has repeatedly joked about Canada becoming a state. In his recent NBC interview, he complained that we are “subsidizing Canada to the tune of over $100 billion a year,” continuing, “If we’re going to subsidize them, let them become a state.”1 Trump has used this rhetoric that the US is losing in trade and the trade deficit (which is what he means by subsidizing) shows that for a while.

Maybe Trump’s just playing to his base, or perhaps he has a fundamental misunderstanding of trade. Trade between countries can be mutually beneficial even if there are some “losers.” Trade deficits aren’t necessarily bad and certainly aren’t evidence we’re losing at trade or “subsidizing” another nation. Lastly, there’s not a huge difference between trading in different US states and trading in different countries. If you think trade deficits are bad, then you should be equally concerned for the individual states that currently have trade deficits with Canada and continue to do so even if Canada was declared the 51st state.

Trade isn’t zero-sum

As I write this, I’m sipping my V8 energy drink. I chose to buy it because I preferred to fuel my caffeine addiction over the dollars I had, and V8 decided to sell it because they valued the dollars more than the drink they produced. So we exchanged, and both of us are better off overall. That doesn’t mean there was no cost; I lost my dollars, and V8 lost their drink, but in voluntary exchanges, both parties expect to benefit; otherwise, one party would have declined.

So, transactions between individuals don’t necessarily have to be zero-sum. All a free trade policy does is allow individuals to participate in these voluntary exchanges across political borders. The fact that an exchange happens to take place between a national and a foreigner makes it no less mutually beneficial. There’s good reason to believe free trade is not mutually beneficial if the voluntary exchanges that comprise it are mutually beneficial.

A basic model of comparative advantage can also show how trade makes us all better off. Countries have a limited number of resources that can be used to create different combinations of goods and services. Depending on a country’s geography, labor force, capital markets, and even things like regulations, countries can be better or worse at producing certain things. Even if a country is better at making everything than another country, countries can be comparatively better at producing certain goods because of opportunity cost.

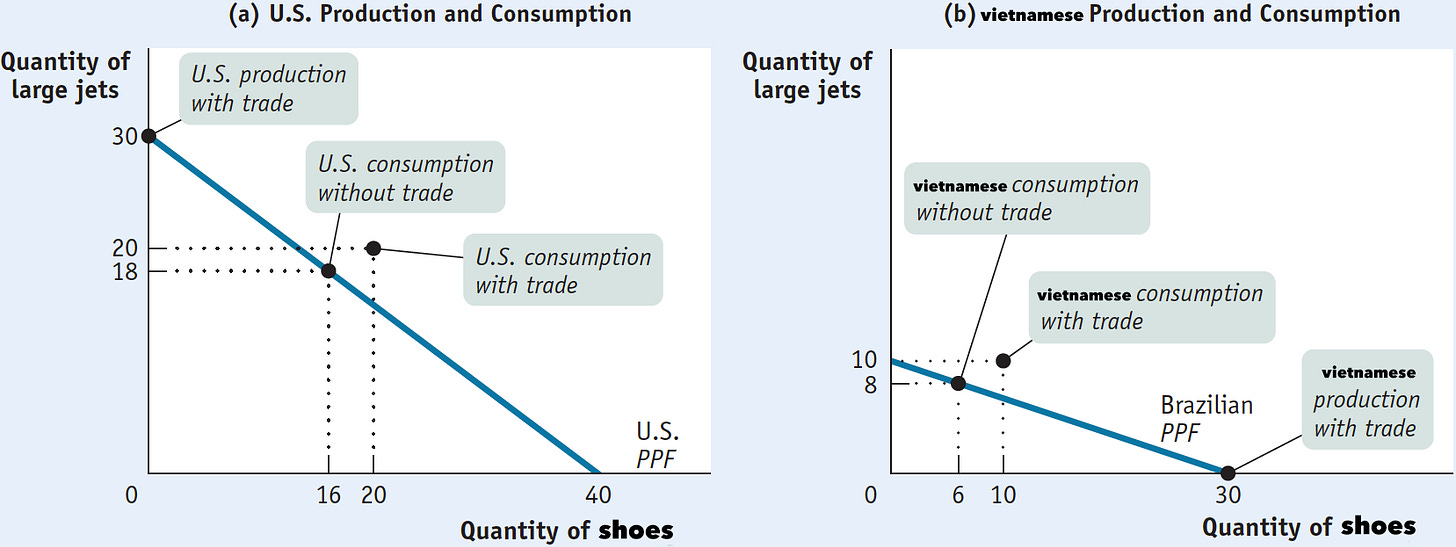

Just take the US and Vietnam. In an absolute sense, the US is more efficient at producing shoes than Vietnam. But for the US to produce shoes, it has to give up a given amount of, say, aircraft production. Vietnam also has to sacrifice some amount of aircraft production to produce shoes. But if Vietnam has a comparative advantage in producing shoes, it can produce more shoes than the US can by sacrificing the same amount of aircraft production.

Conversely, the US can produce more aircraft than Vietnam by sacrificing the same amount of shoe production. The implication is if a country specializes in what they have a comparative advantage in each country can obtain a greater quantity of at least one good than if it had produced both goods for itself. I didn’t go into much detail, but if you want more, you can read a little from an introductory textbook or watch a YouTube video.

We can show the effects of this in a graph. First, we plot all the possible combinations of what either country can produce. Every point on the diagonal line represents an efficient use of their resources, whilst a point on the outside of the line represents a level of production that’s impossible for them to achieve. With trade, however, both countries can consume an amount of goods outside the line, which would be impossible for either to produce on their own.

I think there’s some confusion here because economists like to state that there are “winners and losers” in trade. Take a tweet that made the round on econ Twitter recently:

I hope I’ve illustrated why trade and exchange don’t have to be zero-sum, and someone tried to use similar logic in response to him:

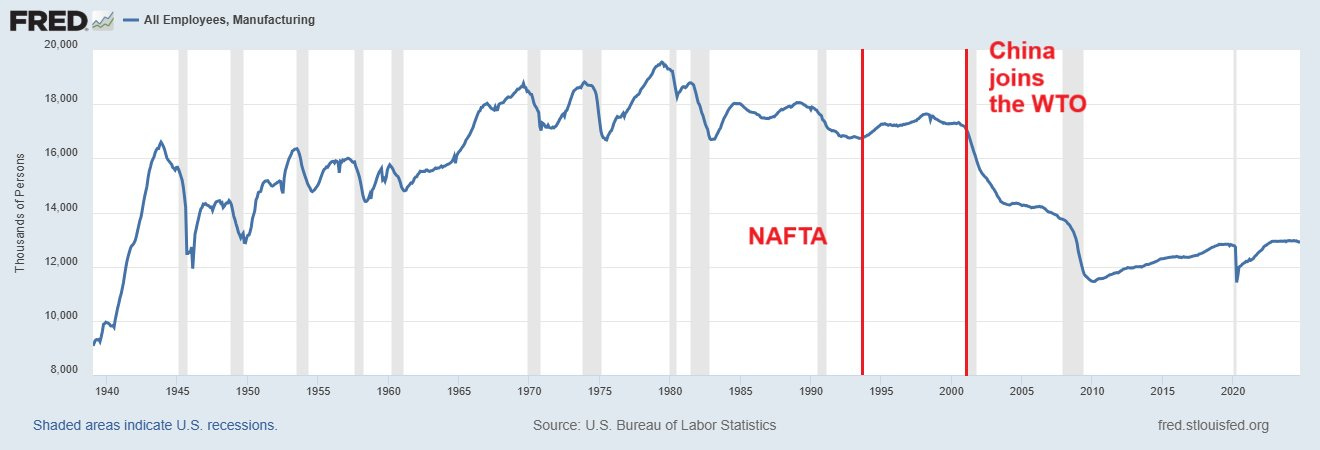

Here, he resorts to pointing out there were indeed “losers” in the US when we began trading with China, primarily those whose manufacturing jobs were offshored. But the economist phrase “winners and losers from trade” doesn’t mean that a country lost overall while another country won overall. Instead, it means that within a country that is better off overall, there were some people made worse off whose loss was offset by the gain everyone else experienced. Just because there is a cost to something doesn’t mean you are worse off overall. You recognize this with every exchange you participate in, where you pay a cost (say dollars) for something you value more (say V8 energy).

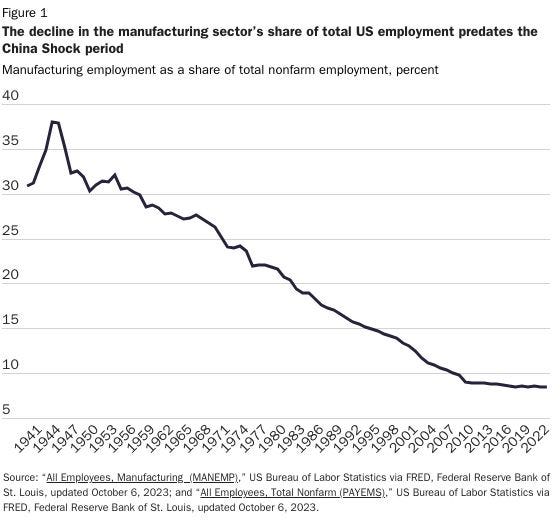

It’s also worth noting the cost of manufacturing because of trade is often overstated, as it is here. Around 5.8 million manufacturing jobs were indeed lost in the so-called “China shock” period between 1999 and 2011. Some of those jobs were lost because we began trading more with China, and they have a comparative advantage in a lot of labor-intensive industries. Still, a lot of those jobs were also due to advancements in technology and automation. You can see manufacturing output grew over this entire period before stagnating after the Great Recession despite the decline in manufacturing employment.

Estimates of how much of the job loss was due to trade vs technology vary, but the highest I’ve seen is Autor, Dorn, and Hanson 2016 who estimate at most 2.4 million jobs were to trade. I list some other estimates in this tweet.

Manufacturing’s share of employment has been on a steady decline in America for decades with no visible shifts that would indicate the China shock was responsible. Although, the absolute number of manufacturing jobs did decrease during the China shock.

Eventually, I’ll write a full blog post dedicated to why trade isn’t responsible for the loss of manufacturing. For now, Martin Wolf summarizes why this is the case in his article based on a model provided in the book Behind the Curve — Can Manufacturing Still Provide Inclusive Growth?. Scott Sumner also has a short blog post about this.

The last thing I’ll note is we still see declines in manufacturing employment in countries with trade surpluses, so it looks like tariffs can’t save us here.

Trade deficits aren’t really bad

The trade deficit shows the difference between the amount of goods and services we sell to other countries (our exports) and the amount of goods and services we buy from other countries (our imports). Trump’s logic is fundamentally mercantilist, he presents the trade deficit as evidence we are “losing” at trade because we import more than we export. I don’t exactly what he means by subsidy, but if he believes every country should export more than it imports then we are in effect helping many other countries by buying their exports. Trump and the mercantilists fail to consider that a country isn’t wealthy because it hoards gold bars, but rather when it maximizes consumption possibilities. Secondly, the trade deficit largely reflects America’s favorability from foreign investors.

When you go to work, you produce things for other people, which is a cost to you. You’re compensated for that loss with an income, which, in turn, lets you consume what others produce. Similarly, exports are costly because we use our resources to produce for other countries. We are compensated for this loss with foreign currency with which we can purchase goods produced with other countries’ resources, to satisfy our consumer preferences. Trading with other countries increases the amount of goods and services consumers can actually utilize. This is what real wealth is.

Remember however that trade is not zero-sum, so even countries that run trade surpluses can benefit. That’s because when a country runs a trade surplus it is left with a surplus of foreign dollars that it invests abroad. That investment is also mutually beneficial, it grants someone the opportunity to start or expand their business and the investor a future return (at least if all goes well). Conversely, if a country is running a trade deficit it doesn’t receive enough foreign currency from exports to buy all of its imports. So it must receive foreign currency from investment in domestic industry.

The amount of investment and lending flowing in and out of a country is referred to as the financial account (or capital account). Importantly the capital account and trade balance must exactly cancel out. So if a country has a $50 billion trade deficit, it must have a $50 billion capital account surplus.

Part of the reason the US runs a trade deficit is because we’re such a good place to invest in. If Europe invests a lot of its currency in America, that increases demand for American dollars and increases the supply of Euros, both of which make the US dollar more expensive relative to the Euro. When the US dollar becomes more expensive or “stronger”, we can buy more foreign currency allowing us to import for cheaper. The capital account surplus also means investment opportunities in America are so large that Americans alone can’t finance them. Instead of forgoing these investments, foreign capital is brought in.

New Ideas from Dead Economists showcases Republicans haven’t made any progress on this issue since Lincoln:

Abraham Lincoln put one protectionist argument pithily: “I don’t know much about the tariff, but I do know if I buy a coat in America, I have a coat and America has the money—if I buy a coat in England, I have the coat and England has the money.” He was right—he did not know much about the tariff… If Lincoln buys the London coat he prefers, he cashes in some dollars for British pounds. So someone in London now has dollars. Londoners do not give up pounds just to wallpaper their flats with greenbacks. The Londoner will either (1) buy an American product or (2) trade in the dollars for pounds. If she buys an American product, Lincoln is happy because he preferred the London coat, and the Londoner is happy because she liked the American good. If she dumps her dollars, she will dump them on someone else who wants to buy American goods.

Furthermore, the US is the world reserve currency. That means US dollars are almost always in high demand, which keeps our dollar expensive. An expensive dollar keeps imports cheap for us but makes our exports more expensive for other countries to buy. So it looks like Mr. Trump’s 5th core promise to “STOP OUTSOURCING, AND TURN THE UNITED STATES INTO A MANUFACTURING SUPERPOWER” isn’t happening without breaking his 13th core promise to “KEEP THE U.S. DOLLAR AS THE WORLD'S RESERVE CURRENCY”.

So trade deficits don’t show if anyone is winning or losing at trade, and both can be beneficial to a country and those who it is trading with. Right now you have a trade deficit with your grocery store but that doesn’t make the relationship any less mutually beneficial.

There's not a fundamental difference between states tariffing each other and countries tariffing each other

I’ve used trade between individuals as an analogy to trade between countries. Really, they aren’t all that different. The same fundamental principles of voluntary exchange and comparative advantage apply equally. So, here comes the hard question for protectionists like Mr. Trump: If it’s bad that the US has a trade deficit with Canada, how will the problem get any better if Canada becomes a state? Wouldn’t Canada still have a trade deficit with the other 50 states? Why is it not equally as bad if California has a trade deficit with North Carolina?

Sometimes trade between countries can be complicated by differences in domestic regulation. I’ll make a full post about this one day but the differences in regulation don’t make it any less of a net benefit to trade. The line between an “artificial” comparative advantage due to regulation and a “natural” one isn’t partially clear or relevant. Really the case for free trade is unilateral and it’s almost always in a country’s best interest to engage in free trade regardless of another country’s regulations or trade policies.2

But regulations also differ between US states, should California tariff North Carolina because the minimum wage is $16.50 an hour in California but only $7.25 in North Carolina? Furthermore, Canada is a developed country with similar regulations, and the two indexes I found both show it has higher labor standards than the US.

If you think trade is zero-sum and/or trade deficits are bad then you should support states tariffing each other as much as countries tariffing each other. Consider tariffing your grocery store too. If Canada were to become a state trade would only increase. You could measure Governor Trudeau’s trade deficit with the rest of the 50 states in the US, and it would be about the same as it is today and equally irrelevant. Maybe it would change a little, but only because states can’t legally tariff each other. So if Canada's statehood avoids 25% tariffs on Canadian oil to the Midwest then count me in.

He also complained about Mexico, but I believe this is the only time he’s talked about Mexican statehood, whereas he has repeatedly mentioned it with Canada. It’s also absurd we’re talking about this before Puerto Rican statehood.

National security concerns can also prop up with other nations. However, Trump was focusing on economics so I did as well. Canada is one of our closest allies and it’s in NATO. Worse comes to worst I don’t its military poses a significant threat to ours.

Countries dont win or lose but people do win or lose when it comes to trade policy. When a shoe manufacturing plant off shores then the 3000 works lose their jobs. Those workers would then be losers as a result of trade. Yet what should be focused on is the net benefit of the country as a whole. Job loss is a net benefit for the country because we would generally get lower prices on importanted products.